A poem selected by our director Nicholas Allen, Baldwin Professor in Humanities

Dear friends,

Seamus Heaney grew up in the flatlands by Lough Neagh, not far from the eel fishery in Toomebridge, known to those of you who like our grim ballads as the site of Roddy Corley’s execution after the 1798 rebellion. That insurgency aimed to unite Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter in one Irish republic. Corley’s demise may or may not have happened as the song has it, but it makes for a rousing ballad, which The Dubliners performed with brio.

Lough Neagh is one of Europe’s largest freshwater lakes and is fed by both the Blackwater and the Bann, which alone flows into the Atlantic. Heaney has been read for a long time as a poet of landed place, of bog and farm and townland. Less observed is his attachment to water, from the dripping pump in Mossbawn’s yard to the streams, rivers and lough that led to the world from his door.

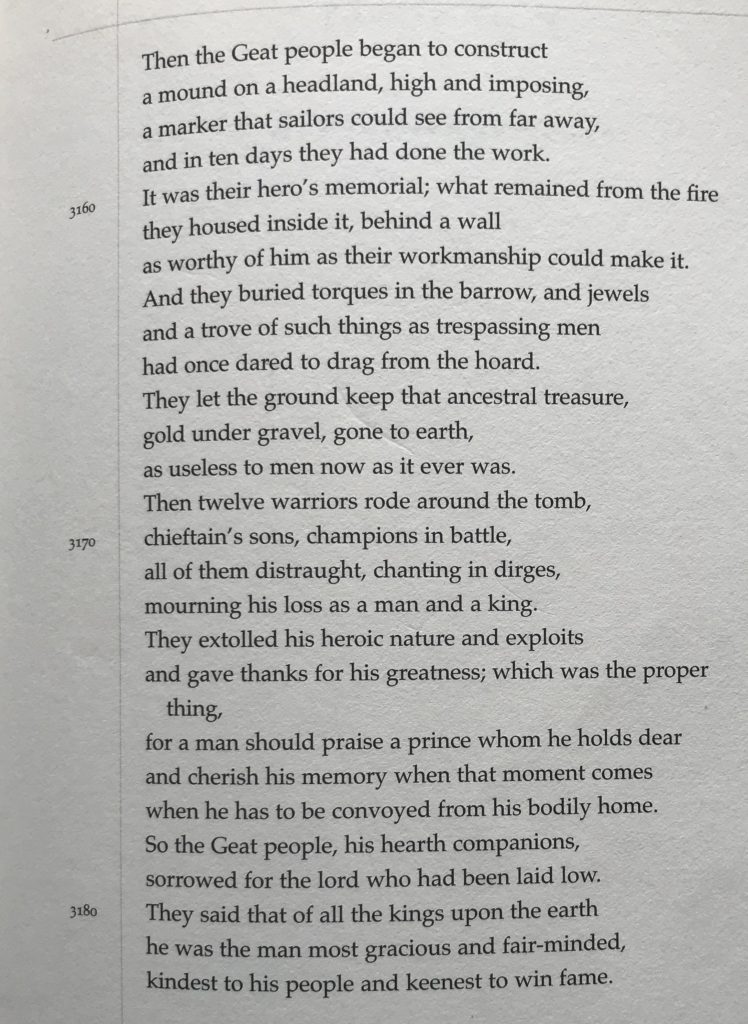

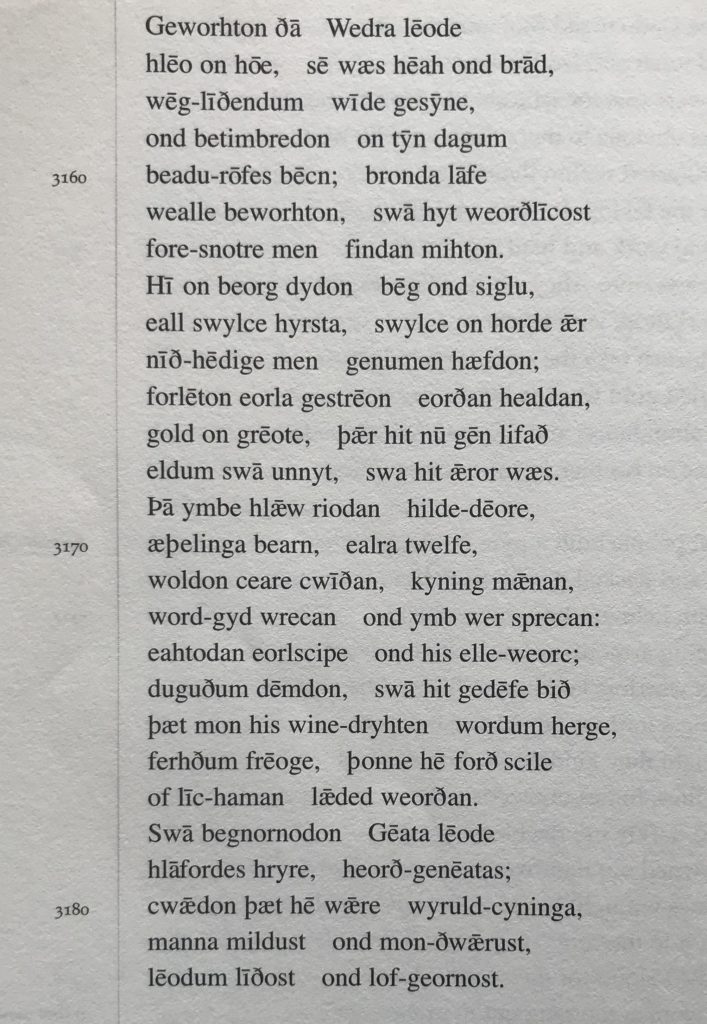

It is fitting then that “Eelworks” is a poem of leaving and returning, a meditation on childhood, language and love (think, for example, of those lips in the last lines). In this poem, art is a selkie, a Scots word for the seal-folk, whose skins, like those of the eels in the poem, are a subject of human fascination. “Eelworks” is an elemental poem, made of the fabric of Heaney’s community, of his past, and of his life-long understanding of poetry. It is a catch too of other poems that fed Heaney’s imagination, such as the hint of Yeats in the fishing rod from “The Song of Wandering Aengus.” Next week we will join Beowulf in his foray against Grendel but for now notice the kennings that braid the fourth section of the poem, those pairs of words chained together by hyphens from which the old Germanic languages made metaphor (and my favorite of these is “hron rade,” or whale’s path, which was the sea).

In the summers I regularly pass the eelworks on the road to my parents. It is an unremarkable place on the surface, a jetty of steel gantries across the Bann mouth, a gallery of herons, rusty sheds. It makes me think how magical is poetry, to summon the imagination from the everyday, clad in the hardy raiment of memory, weathered by experience and returned, as in “Eelworks,” to simple beginnings that endure.

Next week we land with Beowulf on shores further north, “we gardena ingear dagum,” Spear Danes in days of old. But I get ahead of myself, and I’ll have a story to tell you then about those opening lines.

Keep going,

Nicholas

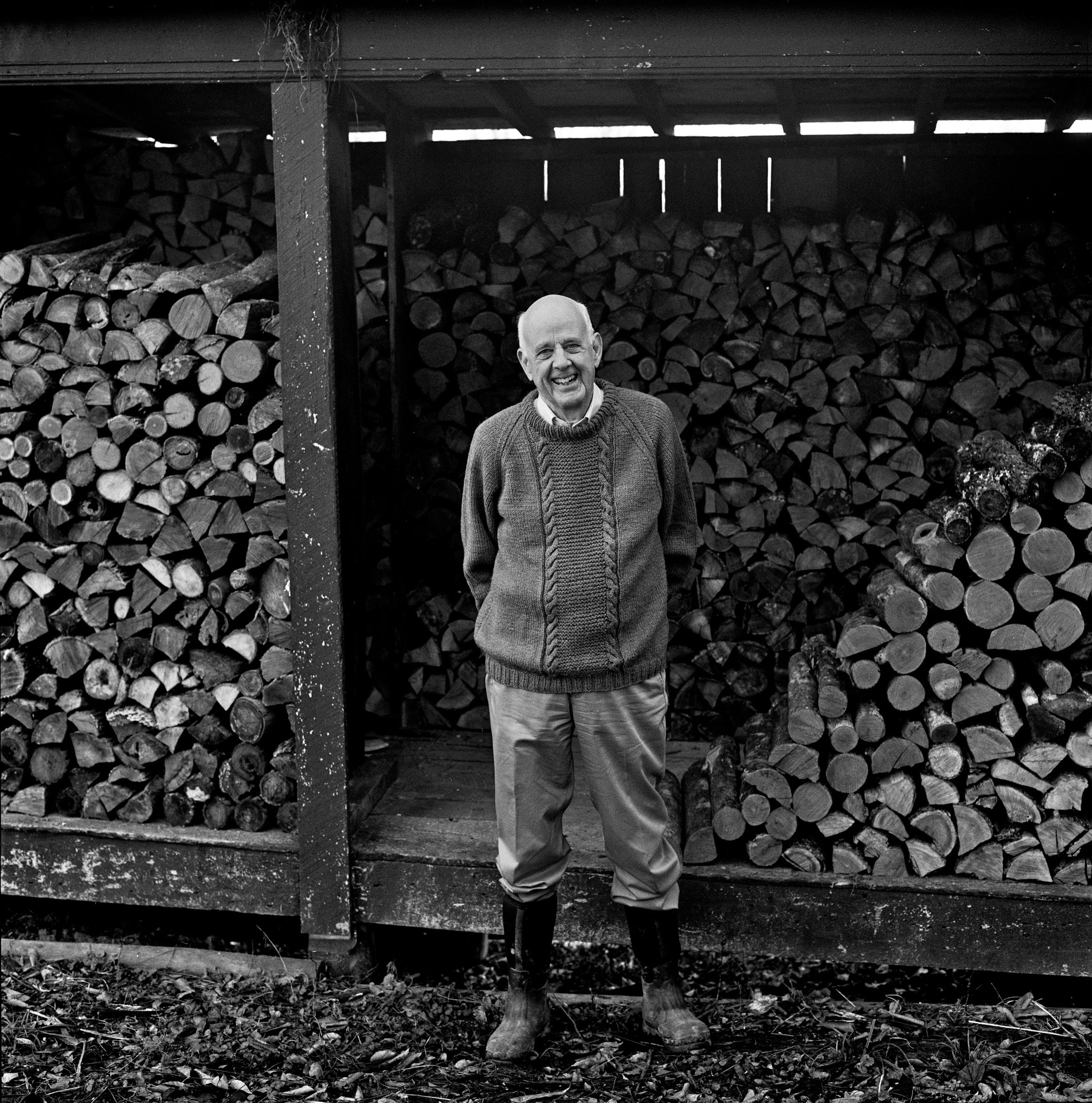

Seamus Heaney

from “Eelworks”

ii

Cut of diesel oil in evening air,

Tractor engines in the clinker-built

Deep-bellied boats.

Landlubbers’ craft,

Heavy in water

As a cow down in a drain,

The men straight-backed,

Standing firm

At stern and bow –

Horse-and-cart men, really,

Glad when the adze-dressed keel

Cleaved to the mud.

Rum-and-peppermint men too

At the counter later on

In her father’s pub.

iii

That skin Alifie-Kirkwood wore

At school, sweaty-lustrous, supple

And bisected into tails

For the tying of itself around itself –

For strength, according to Alfie.

Who would ease his lapped wrist

From the flap-mouthed cuff

Of a jerkin rank with eel oil,

The abounding reek of it

Among our summer desks

My first encounter with the up close

That had to be put up with.

iv

Sweaty-lustrous too

The butt of the freckled

Elderberry shoot

I made a rod of,

A-fluster when I felt

Not tugging but a trailing

On the line, not the utter

Flip-stream frolic-fish

But a foot-long

Slither of a fellow,

A young eel, greasy grey

And rightly wriggle-spined,

Not yet the blue black

Slick-backed waterwork

I’d live to reckon with.

My old familiar

Pearl-purl

Selkie-streaker.

…

vi

On the boarding and the signposts

‘Lough Neagh Fishermen’s Co-operative’.

But ever on our lips and at the weir

‘The eelworks’.