Your weekly poem, May 26: “Beowulf” translated by Seamus Heaney

A poem selected by our director Nicholas Allen, Baldwin Professor in Humanities

Dear friends,

Today we begin a few weeks’ foray into a world of monsters, mead-halls, providence and revenge. In preparation for our journey into Dane land we must think first of the thin threads that tie this far past to the present, the old languages of northern Europe brought across the wintry seas to what would one day become England, where Beowulf was later composed. The three thousand lines of Anglo-Saxon verse are our only bridge to the society that the poem sketches, and even this is imperfect since the poem seems to have been written in the early eleventh-century, which is long after the sixth-century period when the poem is set, and which explains the many Christian references in a pagan text.

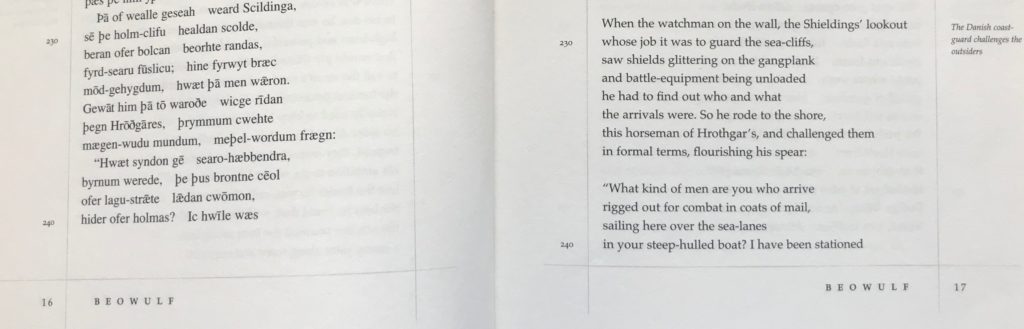

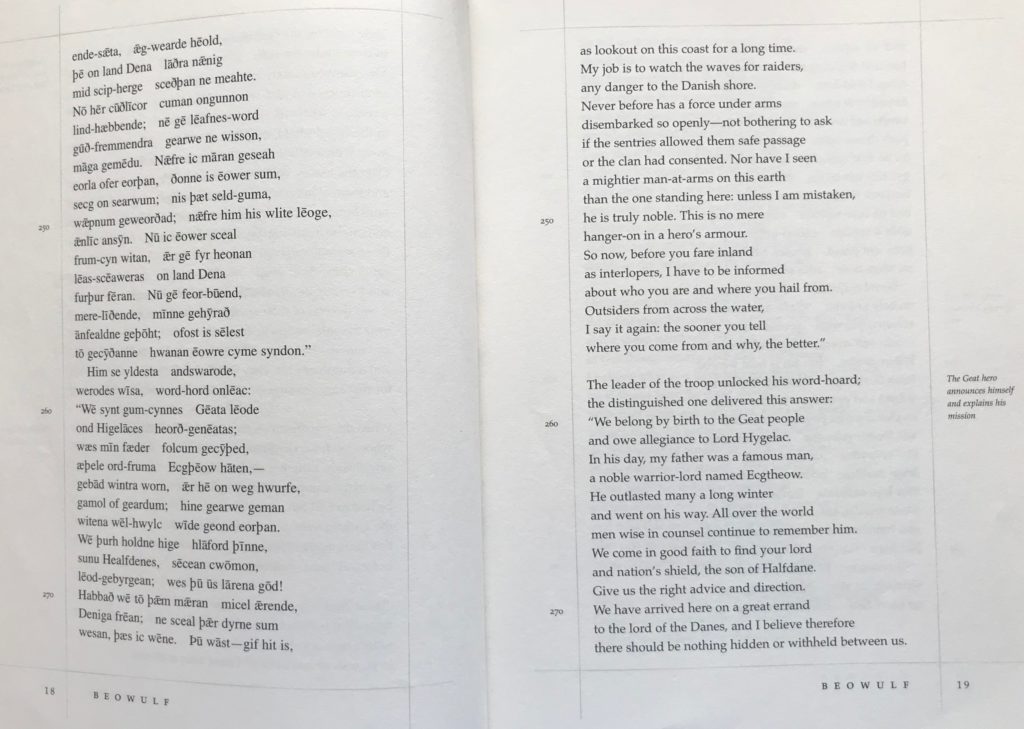

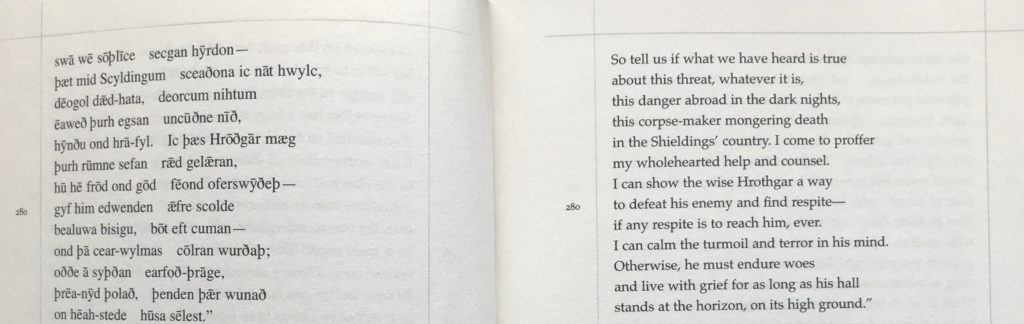

The British Library is a wonderful resource to learn more about Beowulf, in particular the survival of the manuscript through the generations, surviving fire and fragility. I invite you to take a moment to listen to the poem in the original Anglo-Saxon and let the strangeness of the words wash over you. You might even use the text below to try to read the lines that Seamus Heaney made his version from. Do this in your garden and if nothing else your neighbors will have something to think about during the week to come. Or, if you are looking for some fictional distraction based in the intrigues of pre-Norman England, I highly recommend to you The Last Kingdom, which has all the bluster and intrigue we could hope for in our contemporary imagination of this very far past.

Seamus Heaney studied Beowulf as an undergraduate in Queen’s University in Belfast, as I did much later. I loved our small tutorials in Anglo-Saxon, puzzling over poems like The Seafarer and The Battle of Maldon, the solitary, the elegiac and the narrative combined. Heaney undertook to prepare a version in the 1980s while he visited at Harvard, but only got around to finishing it much later, in 2000. The connections between Ulster-English, with its fricative phrasing and the clacks and clicks of kennings, kings and war, spoke true to Heaney’s ear, as you can read in the excerpt below and hear in his own reading. This describes Beowulf’s arrival with his war-band in Denmark from Geatland, or what is today southern Sweden, and has all the linguistic flourish of arrival in a culture that proceeded from power and precedent. Beowulf is there to save Hrothgar from the attacks of Grendel, and if you bear with me over the coming weeks we shall follow him in his trials as one battle becomes another.

Be well,

Nicholas

Baldwin Professor in Humanities

Director, Willson Center for Humanities and Arts

University of Georgia