Your weekly poem, June 9: “Beowulf” translated by Seamus Heaney, conclusion

A poem selected by our director Nicholas Allen, Baldwin Professor in Humanities

Dear friends,

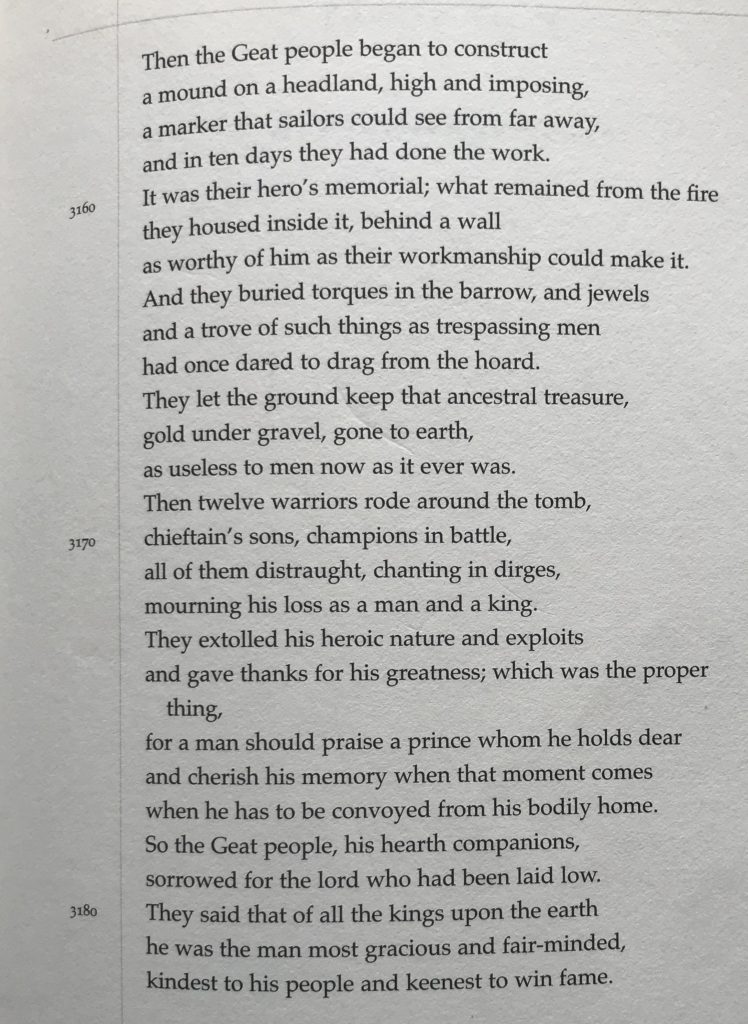

Epic poems tell the stories of heroes and their deeds. In doing so they tell us something both of the cultures that produced these figures, and of the art that casts them in poetic memory, which can be as far removed from fact as fiction. That distance is not a deficit but an opportunity to consider the things the artwork might not mean to say, or consider important. So in Beowulf, the hero kills Grendel, the monster’s mother, and a dragon, jealous of its hoard. This last is his undoing, for, to his companion Wiglaf’s regret,

Often when one man follows his own will

Many are hurt…

There is no epic, and no poetry, without our collective agreement to meet imaginatively at the work of art. In Beowulf, this requires a commitment to truth, honor and the giving of the self to others. In that society, reputation was not a fixed point but a constant readjustment, which even the most celebrated of heroes sometimes failed to make. Greatness was no end in itself, but a partner to the daily solidarities that kept a society together, from the mead hall to the shield wall. As the poem suggests, the darkest monster of all is drawn from the self-regarding specters of pride and greed, Beowulf unheeding of the advisors who bid him leave the dragon sleep, his mourning people haunted now by the vision of the Geat woman who cries “a wild litany of nightmare and lament.”

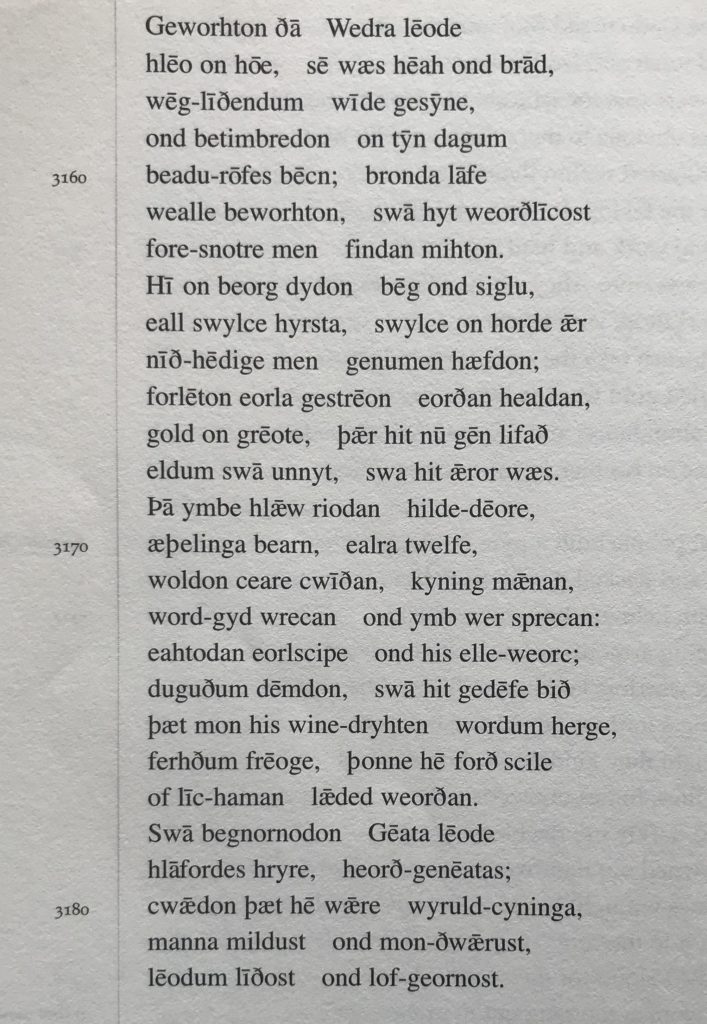

That we can read these words so many centuries later says something more optimistic about human society, which is its capacity for co-operation, that mutuality which is of the substance of that most radical practice, of reading. Beowulf comes to this ethical realization in its own way, true heroism a balance of grace and fairness, and expressed in a language the form and sound of which reminds us to keep our minds open to strangers as envoys of a greater understanding:

Swã begnornodon Gēata lēode

hlãfordes hryre, heorð-genēatas,

cwædon þæt hē wære wyruld-cyninga

manna mildust ond mon-ðwærust,

lēodum līðost ond lof-geornost.

Thank you for your good company over these past weeks. We will gather ourselves again in the mid-summer. Until then, read and be well.

Best,

Nicholas