New web-based project tracks U.S. Army deployment in Reconstruction South

Mapping Occupation, a recently launched web-based project by University of Georgia and City University of New York historians, provides the first detailed look at where the United States sent its troops to occupy the South after the American Civil War. This new view of the Army’s role sheds new light on the complex landscape of Reconstruction.

The project was authored by Gregory P. Downs, an associate professor of history at the City University of New York, and Scott Nesbit, an assistant professor and Willson Center Digital Humanities Fellow at the University of Georgia. It builds upon Downs’ book, After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War, to be published by Harvard University Press on April 9, 2015.

The Mapping Occupation site was developed with the support of the American Council of Learned Societies, with assistance from Information Technology Outreach Services at UGA. It is affiliated with the Willson Center Digital Humanities Lab, which will open in April 2015.

After the Civil War, the U.S. Army was the key institution that freed people used to attempt to defend their newly won rights. Yet its importance has been largely forgotten or misunderstood, as early historians exaggerated the pains of “bayonet rule” for white southerners and many later historians, to combat these myths, imagined that the Army was of little consequence in comparison to other postwar government agencies.

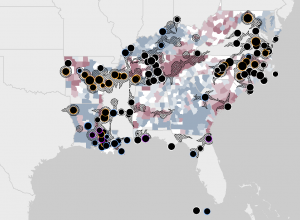

But no one actually knew where the Army was located during the years after the Confederate surrender. Mapping Occupation is the first-ever dataset showing where the Army was during Reconstruction, compiled from tens of thousands of reports at the National Archives. Rather than being a small or insignificant actor in Reconstruction, the Army held almost 1,000 posts in the South during Reconstruction and remained there for a surprisingly long period of time.

“Knowing where the Army was and what it was doing will change many of our interpretations of Reconstruction,” Downs said. “The way we think about Northern support for Reconstruction and about the immense challenges that Reconstruction faced on the ground will change as we reckon with the Army’s role. Because Reconstruction is so central to the end of slavery and the creation of constitutional rights we still enjoy, it is crucial that we understand how those rights were made and how they were rolled back. If we assume that the United States did not try to remake the South, then we lose track of the difficulty of creating rights and the even greater problem of sustaining them in the face of intense resistance.”

In fact, Nesbit said, “now is the time to rethink what Reconstruction meant and means today. One hundred fifty years after Reconstruction began, the United States continues to struggle with the questions it raised then: how does the U.S. work to change societies after chaotic wars, if it should at all? And what role does the federal government have in upholding the rights of citizens when they are subject to abuse from local governments? These questions have not gone away.”